We’ve finished our most recent dissertation cycle here at Northampton. The marking is done and the results have been released. It seems a useful time to reflect as I prepare meetings to discuss projects with students for next year.

We’ve had some great results, some fascinating dissertations, some of them first class. As the convenor of our dissertation module and a supervisor I have the pleasure of seeing individual projects through to completion as well as seeing the ‘whole picture.’ I’m the first to see the overall results which is very exciting!

Seeing students excel in their dissertations is among the most rewarding parts of my job. The dissertation is the culmination of their studies, where they test all the skills they have acquired and really think deeply about the subject in the context of a detailed research project. It is when they truly become ‘historians.’

Some of the results are publishable and some do get published and that is tremendously satisfying for us and the students.

Students also really enjoy the process overall. We are consistently told by students near the end of their studies (often at graduation) that it was their favourite experience at university. They get to focus on their specific interests, develop their own ideas.

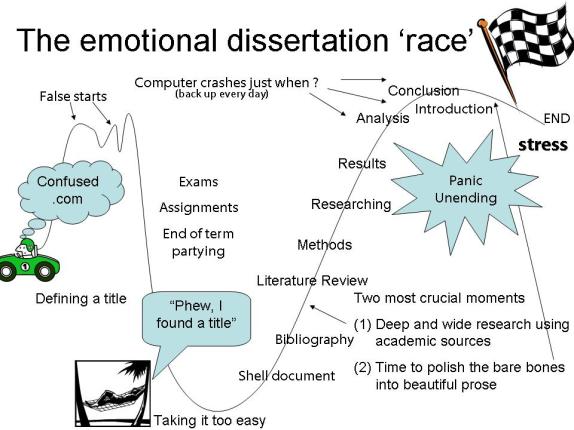

That doesn’t mean, of course, that it isn’t hard work, difficult and stressful. Developing high quality research and making it worthy of good rewards is all of these things.

So here is a brief description of what a dissertation is and some tips for succeeding with the dissertation and having a good experience – some dissertation do’s and dont’s that we communicate to our students at the start of the process.

Every project is different and only you and your supervisor know precisely what you should be doing from one point to another but these guidelines generally apply to most dissertations. This is a longer blog than I usually write but there’s a lot to get through!

What is a Dissertation?

A history dissertation is a written study (Most universities specify around 10,000 words) of a specific historical topic/theme/person/event.

It forms a significant part of the third year of an undergraduate degree (many universities, including us, double weight them so they count for two modules).

It should be based around a series of primary sources (the volume and type depends on the project) and should include a comprehensive review of the existing historical literature (this is usually done in the introduction).

Dissertations are not ‘taught’ in the way that other modules are – they are individual projects supervised by academic members of staff.

We provide whole group guidance for our third years in four sessions across the academic year (some other institutions do this, some don’t). But in the main your experience will involve one-on-one supervisions.

A dissertation is not a long essay and it is not a source analysis.

Unlike essays the argument of the dissertation must be based around and driven by primary sources and the secondary sources (the books, articles etc) are used to contextualize and help you interpret the findings from the primary sources.

Unlike source analyses the sources must be used to build the overall argument – merely commenting on their content is not enough. Your footnotes in the main chapters should mainly be to your primary sources – this is why we call them ‘primary.’

Some universities (including ours) build in other assignments to the dissertation module (we have a Viva which forms 10% of the overall grade). These are important staging posts towards the final product. But the showpiece is always the written dissertation and that’s the piece of work you’ll have on your bookshelf after the deed is done.

Do’s and Don’ts

1. Choosing the Topic: Picking a topic is subject to a range of different factors: In short it must be interesting to you, feasible in the time (1 year) and space (10,000 words) you have, possible with regards to primary source material and worthy of study.

DO pick a topic you are interested in, DON’T pick something because it seems easy. You will be studying this topic for a whole year and it will be really tiresome if it’s something that doesn’t really interest you.

DO take time thinking about your topic and speak to your prospective supervisor in detail about this (probably in several different meetings). DO read around the subject. DON’T rush this – if you change your mind midway through the project it will almost definitely impact negatively on the outcome (are you listening Brexiteers?)

Ask yourself a series of questions. What period of history am I interested in? Am I a political, military, social, cultural or economic historian? What particular themes have I enjoyed on my modules, is there anything I particularly enjoyed (think of the assignments you have done).

There’s no problem starting with quite a broad topic then narrowing this down as you scope the project (see below).

But the topic needs to be worthy of study in the sense that there needs to be a rationale, it needs to be something that is of interest to others and some importance, not just interesting to you. In the introduction you’ll need to justify the topic, why are you studying it and what the importance of it is.

2. Scoping the topic: DO scope your project carefully before deciding on it and DON’T stick stubbornly to your beloved subject if it becomes clear it can’t be done.

Are the primary sources available and can you use them? If they are written in a foreign language will you be able to read them? Is there much more that can be said about the topic? Can the project be done in one year and can it be given sufficient justice in 10,000 words? – (a new history of the Second World War is probably not feasible, neither is a new history of the Industrial Revolution).

The final product will be only four times the length of this blog (we exclude footnotes and bibliography) so what at first seems a daunting volume of writing will soon become quite a restrictive format.

Work spent early on planning and researching the project (as opposed to researching the subject) will be some of the most valuable time you’ll spend on it.

3. Organising your work: DO start work early. DON’T leave it until the beginning of the third year. You’ll have a very busy and hectic final year anyway, so don’t make it even more stressful.

Make sure you start the project over the summer between the second and third year. Engage with any preparation modules in the second year – ours is called ‘Research Skills in History.’

Over the summer get some reading done, get to the archives and start thinking about a structure – very valuable time, especially if an unexpected personal or family issue means you have to take some time off in the third year.

You need to take a break from your studies, that is important, but there should be time for work too.

DO work consistently on the project at an even pace, DON’T work in ‘fits and starts.’ Try to work on the dissertation each week so you remain ‘in contact’ with the research.

Successful academic research requires us to create a space in our minds that is devoted to the project – it becomes part of us (not physically of course but that’s how it feels). A few weeks away will distance you from the project and you’ll need to spend several days (or more) ‘getting back into it.’

As academics with teaching and admin to take care of as well as research we’re all well aware of that. I’m looking forward to getting my teeth into my new project on the history of emotions over the summer.

4. Supervisions: DO go to meetings with your supervisor and DON’T ‘bury your head in the sand’. Missing meetings (often because targets have not been met or little work has been done) will annoy your supervisor and if you make a habit of doing this will leave you flying solo with the project.

Academics require years of training and experience to manage their own projects – the simple truth is students (undergrads and postgrads) need supervision because they lack that experience.

Make sure you pay attention in supervisions and take notes for future reference. Try to stick to any plans and timetables agreed – its best to be realistic when setting these. Above all be honest, supervisors can’t help if they don’t have the full picture.

5. The Reading: DO think about what you need from your reading. You need three main things:

1. The main debates and arguments in your topic area – these are generally found in the introductions of books and articles.

2. The wider context within which your topic sits – this means finding reading dealing more widely with your period and topic so DON’T merely read the small number of books on the history of shoemaking in nineteenth century Northampton if that is your subject. Read about be wider history of that industry and the wider economic history of Britain in that period.

3. Some background and factual details with some examples.

Often students focus on number 3 and neglect the first two. You’re expected to distill and synthesize this material for the literature review in the introduction and to contextualize and compare your findings from the primary sources in the main chapters. Think about this as you read and take notes.

This means the best way is always to read the literature and study the sources in tandem. DON’T do one first then the other. You want the primary and secondary sources to have a productive conversation with each other.

More generally you should use your reading to familiarise yourself with your period/country/locale. As L. P. Hartley wisely said ‘The past is a foreign country, they do things differently there’: L. P. Hartley ‘The Go-Betweens’. You will be a traveler in that foreign place (be it nineteenth century Britain or early modern France etc) so equip yourself with knowledge about the language, culture, politics and habits of that place, even if you’re not a social or cultural historian.

We all know how disorientating it can be in a new place and even if you’ve made visits there before in your modules this will be a much longer and important trip. A good textbook is a wise investment for this purpose, ask your supervisor to recommend a ‘goodun’.

6. Analysing the primary sources: This will be the really fun stuff and is often fascinating and rewarding. DO spend time with your sources, get to know them well, understand their quirks and foibles. Your relationship with the sources should be deep and meaningful, not a brief flirtation. Dissertations require more than a ‘quick look’ at the source material.

It takes a lot of time to read and thoroughly analyse sources, even online ones or visual sources so DON’T under-estimate this in your planning. You’ll understand them more fully if you have a little bit of reading under your belt but you should get to the sources ASAP.

Take a look at this excerpt from an early eighteenth century manuscript letter. How long might it take you to get through a long series of this type of document? What kinds of knowledge and practical skills might you need to use these types of sources? Not all sources will involve the same kinds of skills and knowledge, but all of them will require decoding and careful analysis.

More than anything else the best dissertations are often expressions of the deep knowledge that students have of their sources as windows on the period and area they are studying. If you find previously unstudied sources you stand a chance of finding something truly original but you might also find a novel way of interpreting well known sources.

7. The writing process: DO start writing early and DON’T leave this until the end. As soon as you have some ideas and some material from the sources get on with some writing and send it to your supervisor once drafted.

Start with an easier element of the project and this need not be the introduction (these are often best left until the end of the process). Dissertations need to be drafted, redrafted, redrafted again (possibly several times more) and copy edited before the final read through and submission.

Early writing will expose any weaknesses in the research plan, give you a good idea of what you can fit into 10,000 words, show you the gaps in your knowledge, gaps in your reading and any flaws in technical aspects of your writing remaining into the third year.

If you think that you work best under pressure with coursework, close to the deadlines, this won’t work for the dissertation. In any case you’ve probably not fulfilled your potential with the other coursework you’ve approached in this way.

8. Developing the argument: DO take time to really think about your project and the argument, DON’T rush to pull the trigger on this. What are the central debates and arguments in your topic area? What are the sources as a whole telling you about it?

This may be quite complex, a series of primary sources rarely give us a linear and simple narrative picture. Accept these nuances and acknowledge them.

What is the wider significance of your topic and findings? DO make the most of your work but DON’T be tempted to overstate the significance of your conclusions and simply dismiss all other research in your area.

Conclusions and arguments should be calibrated to the scope of the sources and the length of the study. Historical research is about building on the previous work done, not dismissing it all and starting again.

9. Staying calm: DON’T Panic and DO work through problems.

You will encounter problems, bumps in the road. This is inevitable in a project that lasts a whole year and involves so much work.

If you encounter a problem, either intellectual or practical, speak to your supervisor ASAP. They will have encountered this problem before and are best equipped to help you deal with it.

If you are suffering from stress and anxiety tell your supervisor, they may recommend that you see a counselor. There is no shame in this, its a stressful period in your life so access all the assistance you need to get through it.

The cycles of academic life are one of the things I love about the job – Seeing new students arrive, watching their knowledge and skills develop and seeing their work come to fruition in the dissertation and then graduate – it mirrors my own research cycle: Starting a research project, beginning the writing process, seeing the publication come to completion.

There’s a very pleasing symmetry to it all. I look forward, as ever, to next year’s dissertations. There will be frustrations but there’ll also be some fascinating work and, as ever, some real gems.

Good luck with your projects! Whatever the results don’t be too hard on yourself, if you gave it your best shot that’s all anyone can ask.

Mark Rothery, Senior Lecturer in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century History