17 October 1961

In Black History month it is worthwhile underscoring how minority histories have often tended to be overlooked, covered up, or subsumed under majority narratives and ‘official’ memory. At the time of the Bataclan terrorist attack in Paris in 2015, for instance, the press and media all lamented what they claimed was the biggest loss of life on French territory since the Second World War. This was false. What had been overlooked was the murder of hundreds of Algerians in central Paris on the night of 17 October 1961.

It was the height of the war between France and Algeria. The many Algerians living and working in mainland France were increasingly distrusted by the French government, who feared that they were acting as a ‘fifth column, supporting and collecting funds for the FLN (National Liberation Front), the insurgents leading the war for independence from French colonial rule in Algeria. Harsh domestic policing tactics were employed against Algerians living and working legitimately in France, including surveillance, stop and search, and a curfew which saw Algerians homebound between 7pm-6am.

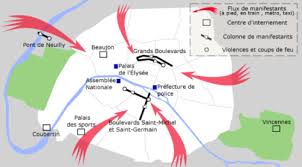

It was a protest against this curfew which sparked the events of 17 October 1961. The Algerian community groups organising the march had emphasised that the protest would be entirely peaceful, and protesters were searched for weapons before they boarded the trains and buses which transported them from the ghettoised peripheries and shantytowns to central Paris.

In 1961, Maurice Papon was the Police Chief in charge of Paris. Papon, who had served as a senior police official for the wartime Vichy regime, and oversaw the deportation of c.1600 French jews to Nazi concentration camps. In 1956 he had also served in Constantine, in Algeria, participating in the repression and torture of Algerian nationalists. Papon’s past clearly did not dispose him to take a lenient approach with colonial subjects protesting on French national territory. However, it is still difficult for historians to establish exactly what precipitated the massacre and on whose orders, for many of the archives related to this incident, and to France’s role and actions in the Algerian war more broadly, are still under wraps.

Around 30,000 marched. By the end of the week 14,000 had been arrested. This fate was far better than many suffered. Police bludgeoned innumerable participants as they exited metro stations. Others were rounded up and taken to the police HQ at St Michel, where, according to eye-witness accounts, Papon ordered their extermination. The bodies of many Algerians were thrown in the Seine.

Evidence of these atrocities was immediately covered up by the Paris police force. Journalists and photojournalists present during these events attest to the fact that they were silenced; that they were threatened; that their copy/photographs/films were confiscated. On the night itself, televised news showed only reassuring images, and the whole incident disappeared from the media by 24 October.

The exact number of deaths is difficult to establish. Some documents and archives have been destroyed, others remain classified. Historian Jean-Luc Einaudi, who has researched the event extensively, and who also challenged Papon in a court case, has suggested that at least 200 were killed on 17 October. British historians House and MacMaster claim that 550 were reported as missing from the shantytowns. At the time, the French government, headed by de Gaulle, with Roger Frey as Interior Minister, admitted only two of the dead. A government inquiry in 1999 concluded 48 drownings on the one night and 142 similar deaths of Algerians in the weeks before and after, 110 of whom were found in the Seine. It also concluded the real toll was almost certainly higher.

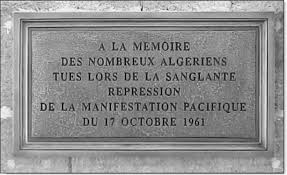

The massacre has often been cited by community activists as an example of ‘confiscated memory’: an event whose existence was denied, the memory of which has been suppressed, and which had long been eliminated from the ‘official’ history of the Franco-Algerian conflict. Activists have sought to reinsert this history into French national memory – some erecting makeshift banners along the banks of the Seine which read: ‘We drown Algerians here’. It was in response to this sort of call for the suppressed memory to take it rightful place in the history of France and Algeria that prompted Paris Mayor Bertrand Delanoë to unveil a plaque on the Saint-Michel bridge of the Seine near to the Police HQ, to those who were ‘victims of the bloody repression of the peaceful demonstration of 17 October 1961’. It was not until 51 years after the massacre, in 2012, that then President, François Hollande, made official comment on the matter, recognising that ‘Algerians legitimately demonstrating for their right to independence were killed during a bloody repression’. The passive voice employed in both the plaque and the statement bear witness to the fact that the French state is still far from being able to acknowledge fully its own part in both the massacre and its subsequent erasure from history.